Artists Ayla Hibri and Tania El Khoury talk empathy, awareness, creativity and influence.

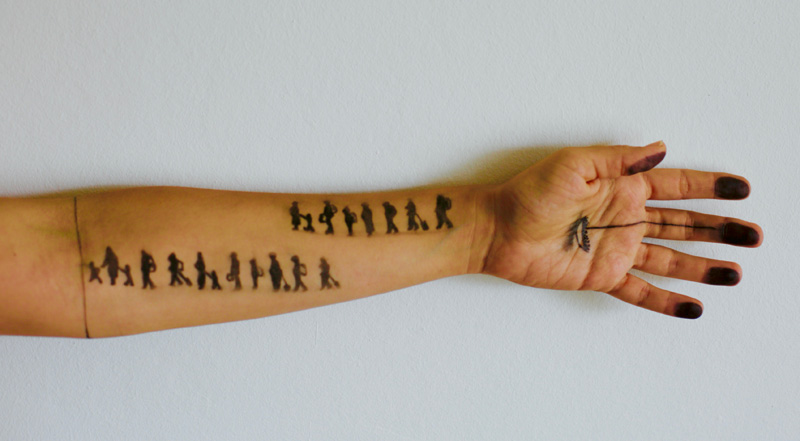

“I am completely drawn to the idea of activism in my work,” says photographer Ayla Hibri. “But the way I do it is indirect and on many different levels, not just political. My revolution is a slow, steady and subtle one.”

Ayla – Lebanese, forthright and articulate – is discussing the idea of activism in art. That form of political or social currency that questions or challenges cultural power structures.

“Photography for me is about empathy and awareness through actively looking and framing specific compositions,” she says. “Every photo I take asks a question. This is what drives me to push the trigger. When I share a photograph, I am also sharing my question, be it about beauty, emptiness, masculinity, femininity, the human condition, mother nature, cities, humour or politics.”

Read:

The life of Dubai’s modern art maven Patricia Millns

Amal Clooney and Cardi B wore the same (amazing) coat

“The more questions we ask ourselves, the more visual data we have, the more open we are to different possibilities. It’s about looking at the world with grace, kindness and acceptance.”

It’s hard not to be an activist in the Middle East. Dispossession in Palestine, corruption and political dysfunction in Lebanon, war in Syria, oppression and misogyny in Egypt. The sources of discontent are endless. Particularly for women. In such environments art is often an expression of resilience and existence, a means of social and political critique. The level of that critique depends, of course, on an artist’s location.

Tania El Khoury, who lives and works in Beirut, has seen her live art described as ‘protest’ or ‘info-activism’, even if she doesn’t necessarily view it as that herself. She creates interactive installations and performances in which the audience becomes an active collaborator.

“I personally do not call my own work activism and I feel that this description silences the conversation around the work itself, since it becomes about its political function and instrumentalisation rather than about how it encounters its audience,” she says. “That said, I did use some tools normally used by activism, such as actions in public space, protest aesthetics, and the methods of info-activism.”

Her work has dealt with marginalised communities, border discrimination, surveillance and profiling in ‘the war on terror’, and land ownership in Beirut.

“They’re always political because everything is political,” she says of her work. “The privatisation of the seashore in Beirut is political. Gender violence is political. This is the world that we live in.”

“I don’t look for problems, but because I work with interactivity and because I work a lot with public space and with the city, it will be a political act to actually choose to ignore the politics of space, for example – to work in a public space and then choose to ignore the fact that it’s very gendered, that it’s very much privatised, that it’s very much elitist.”

Her work with the Dictaphone Group, a collective she co-founded with the architect and urbanist Abir Saksouk, questions people’s relationship with Beirut. Together they have staged performances in everything from cable cars to abandoned railway stations and a fisherman’s boat.

Read:

This Palestinian-American politician keeps breaking barriers

Sheikh Hamdan just showed us Dubai like we’ve never seen it before

The latter was named This Sea is Mine, which explored land ownership of Beirut’s seafront, the laws that govern it and the practices of its users. It did so by inviting people to journey from Ain el-Mreisseh port to Ramlet el-Baida beach, with twice daily performances for five people over a period of 10 days. A sound piece, a research booklet and video were also produced.

“Most of the work that we do is very much about research. And I like that,” says Tania. “I don’t like just political rants. I don’t like people coming on stage and telling us things should be a certain way. It needs to be informed somehow, it needs to be based on some research that can remain, that people can use for other things.

“When you invite audiences to a particular space and tell them it’s endangered, that it’s a space that has this problematic, they automatically build a relationship with it. You sitting at home, or in a gallery looking at (or understanding rationally) what might happen in Dalieh, for example, is very different to you being in Dalieh, looking at the sunset, and understanding that now you’re here, but later you might not be allowed to be here because someone wants to build a resort. It’s about building collective memory with that space, building relationships with that space.”

When we met at Mezyan in Beirut at the end of last year, Tania had just returned from a month-long stay in Tunis, where she had worked in collaboration with a women’s shelter and other activists. This spring she will be in Malta to produce work as part of Valletta’s status as 2018’s European Capital of Culture.

Innovative and exploratory in nature, her work is both immediate and challenging. Fiona Winning, jury chair for last year’s ANTI Festival International Prize for Live Art, noted that Tanis had “foregrounded some of the burning questions of our time by creating resonant experiences that generate conversation and exchange. Tania’s work is urgently needed and we thank her for it”. It was an award that Tania won.

She won largely because of the interactive sound installation Gardens Speak, in which the oral histories of 10 people killed during the uprising against Bashar al-Assad and buried in Syrian gardens are told through found audio. It’s an installation that involves lying on a grave and listening to the whispered stories of the deceased.

Gardens Speak, which was produced in 2014, is still touring, with a show to be held at New York University in Abu Dhabi between 27 April and 3 May. Is there a discernible movement towards increased social and political consciousness from artists in the wider Middle East? If there is, it’s not enough says Ayla, although she and Tania are far from being alone. Only the immediacy of the activism differs.

There’s Sarah Abu Abdallah in Saudi Arabia, for example, Zoulikha Bouabdellah in Algeria, and Hayv Kahraman from Iraq. The aim of Ayla’s photography is not to shock, inform or beautify, but to slow down time and reveal reality in all its complexity and mundanity. Particularly in relation to Beirut. There is no stock imagery of the ‘Paris of the Middle East’ in Ayla’s work. No ‘piece of heaven on Earth’. It is almost, in fact, anti-beauty.

Prior to her return to Beirut, Ayla had spent the best part of a decade jumping between cities, constantly shifting environments to maintain what she calls a “continuum of displacement and discovery”. In doing so she collected visual data on the “poetics and psycho-geography” of places. “My work doesn’t only focus on the Middle East,” she says. “I am a product of the Middle East and I currently live in Beirut, so it is my backdrop at times, but the work I make asks a much larger question that I believe applies to everyone. It is a way of seeing and understanding all the different complexities, mundanities and archetypes that I come across wherever I am.”

“I am not trying to narrow down my research based on geography nor am I trying to make a commentary on the current circumstances.”

Ayla is known as much as a DJ as she is as a photographer. The last time we met was in June last year, two days before she was due to play at Decks On The Beach, a weekly summer party held at Beirut’s Sporting Club in Raouche. She talks quickly and with passion and is worried that her verbal narrative doesn’t do her work justice, but is both affable and welcoming. There are old movie posters and photographs on the walls of her home, while outside is a large picturesque courtyard.

“Art in itself is an act of activism,” she says. “It is about deepening and purifying, creating and sharing. When a painter paints, they are in search of inner wholeness, which is one step up for them and the people they will influence. Of course, that is if it’s done right. And if it’s shared on social media,” she adds with a smile.

With Tania it is possible to discern a sense of annoyance when discussing politics in art. “I feel that the international art industry views people coming from the global south as automatically more political than others,” she says. “That is, of course, a generalisation.”

She is right. There is a perception that all the region has to offer in terms of art – be it visual, film or even music – is in some way political. That war and gender are its main sources of inspiration.

Yet Ayla and Tania surely prove otherwise. Their activism, if indeed that’s what it is, is multi-faceted and nuanced. The question is whether it has any discernible impact.

“I do not know how to measure impact in art,” says Tania. “But I know that some work with political potential may open conversations, challenge concentration of power, and contribute to the writing of history from below, amongst other crucial things.”

Word: Iain Ackerman

Images: Supplied