Iran’s sportswomen face bullying and prosecution for following their dreams. So some have taken to the streets to vent their athletic anger. Meet the parkour women of Iran – Persia’s free-running vanguard.

A GAME OF UNEQUAL HALVES

“Despite what Mr Rouhani had said during his campaign, about involvement of women in his administration, he did not nominate any woman to any ministry.” Shahin Milani is a lawyer at the Iran Human Rights Documentation Centre. He’s been recording Iran’s slow degradation of women’s rights for years; a slide that has placed it 130th of 135 countries surveyed in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (only Cote d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Syria, Chad, Pakistan and Yemen score lower). Last year it was 127th.

Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s new ‘moderate’ president, did eventually appoint female scientist and politician Masoumeh Ebtekar as head of his Department of Environment. But since his election victory in June, Rouhani has done little to curb his county’s prohibitive rules that, for example, bar women from attending football matches.

Iran’s women comprise 60 per cent of college graduates. But lectures and public events are increasingly gender-segregated. Seventy-seven fields of study are off-limits to women, and the lectures that are allowed are frequently gender-segregated, as are a growing number of public events and spaces. “Given the current circumstances,” says Milani, “meaningful change is not possible.”

“Small or incremental change, however, is possible,” he adds. “What I would say is that a number of sports-related events have made positive contributions to the women’s rights discourse in Iran. Women aren’t yet allowed in football stadiums, but the issue has been publicly debated.”

An important milestone was the 2010 Asian Games, held in Guangzhou, China. Among Iran’s 59 medals, which placed it fourth overall, were 14 won by women. This was followed by the very public success of Elahe Ahmadi at the 2012 Olympics in London, who, despite only coming sixth in the 10m air-rifle shooting discipline, received a hero’s welcome when she returned to her home city of Tehran.

Still, though, sport is a deeply divided activity. “To join a team, you have to wear a hijab, which isn’t exactly practical,” says Gilda. “Furthermore, sports facilities are not divided equally between men and women; women practise separately, often in much smaller spaces, if at all. Lastly, the media pays zero attention to women athletes. All of this discourages girls and women from participating in sports.”

A wave of ‘alternative’ sports that have drawn women from the shadows to the spotlight. First it was martial arts, as women showed their strengths and skills to a global Internet audience. “I went to kung fu classes for a while, but I knew that I could never get very far in this sport in a sexist society with hard-line Islamic rules,” says Gilda.

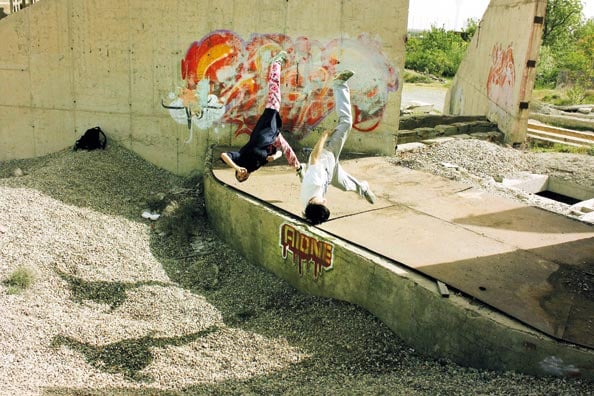

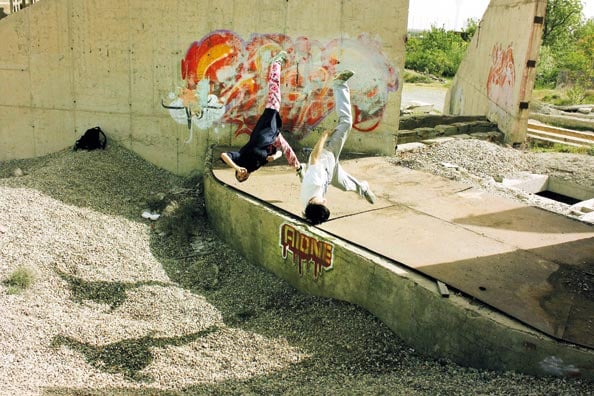

But women have gone further. And parkour is the new frontline.

BREAKING BARRIERS

Fatemeh Akrami was a gymnastics champion, but she needed another thrill. Being from Tehran she was limited to competition with women, tucked away in gyms. She wanted something more. So she jumped, literally, at the chance when a local boy offered to teach her parkour.

Now Fatemeh is one of the best-known female parkour practitioners in Iran. You might catch her somersaulting across Tehran in one of several YouTube videos dedicated to her poise and guile, attributes she dedicates to her childhood years spent grappling gym equipment. Away went the clumsy hijab she’d been used to wearing, and in came her own, shorter outfit and scarf. Her favourite moves are the kong vault and the backflip, which she uses to hurdle Tehran’s tough, ascetic landscape.

“I’ve been doing gymnastics for years,”says Akrami. “Parkour and free-running is so close to gymnastics, and it was easy for me to start because I was a gymnastics champion. But gymnastics is so limited in an Islamic country.

“The main feeling I get from parkour is freedom,” she adds. “It really helped me to feel that freedom in my own country. I could practice together with guys on the streets whenever I wanted to.” People have heckled her, she admits, but people often stop to clap her. It’s something rarely seen in Iran. And a feeling Akrami desperately wants to confer to a younger generation of would-be free-runners.

She continues: “Showing the strong side of women is all I want to achieve.”

Unlike the divided classrooms, offices and gyms, parkour’s open playgrounds are a place where men and women mix, swap tips and help each other out. Mohammad Javad is a 17-year-old enthusiast from Shar-e-Babak, a small southern mining town. It sits in a mountainous strip of Iran next to the prehistoric village of Meymand. “The government is not good but the people are nice. We love all the people in the world,” he says.

Javad practises parkour in the park, in the gym and even in his bedroom. He draws huge inspiration from female free-runners, and it’s one of the few places he and the girls can hang out. “Parkour is a way for women to have abandon,” he adds. “Iranian girls in parkour are hero symbols for other girls and I hope that one day everyone can do parkour without any problem. In parkour, man equals woman.”

For Gilda parkour gave her a chance to break free from Iran’s repressive society, to run at her own pace. “It’s all about speed, unlike the lives of young Iranian women, which sometimes feel like they’re frozen.”

As for Fatemeh Akrami, she’s moved on to even bigger things. Right now she works as a gymnastic coach in Tehran. But her adrenaline addiction has taken her to an even more extreme discipline, skydiving, for which she has to travel to Dubai. Akrami is under no illusions about the tough environment for women all over Iran. She just hopes that she can inspire others to break free and follow her lead. “There are some extreme sports that women don’t usually do here like parkour and skydiving. I’d love these sports to be popular, and some day I’ll be the one who passes her information to all the girls who want to learn.

“I lost years of talent in the gym,” she adds. “I don’t want this to happen to others.”

Words: Sean Williams

Images: Shahin Kamali