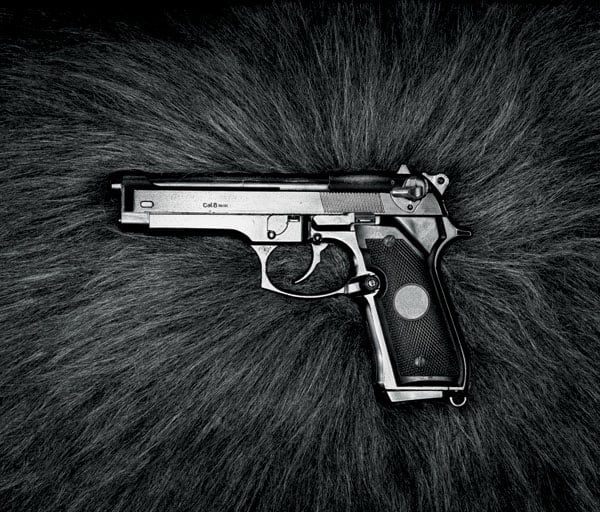

According to New York Fashion Week, fur in fashion is booming. But that’s unlikely to dissuade the Animal Liberation Front from holding back its campaign of destruction. Sean Williams investigates the organisation America calls its number one domestic terror threat (that’s one place above Al Qaeda)…

The prison guards didn’t make life easy for Peter Young. He was screened more than most are for contraband – drugs, shanks (a type of weapon) and shivs (knives) – when he likely to be just sitting quietly reading. Solitary confinement was routine, despite exemplary behaviour. One time, while being transported via plane, Young wore an extra pair of shackles whichno-one else did.

Despite his appearance and manner – “I was, by all accounts, an exemplary prisoner,” he says – Young’s treatment was no surprise. He was a domestic terror threat, prosecutors argued, guaranteed to reoffend. They’d pushed for an 82-year sentence but settled for two after dropping a shaky extortion charge, leaving criminal trespassing, theft and ‘malicious mischief’ on the rap sheet.

“More than anything. I regret my restraint,” Young said, addressing the courtroom. “It wasn’t enough.”

In 1997, Young and a friend drove across America’s Midwest and raided fur farms in Wisconsin, Iowa and South Dakota. Fences were cut and cages opened, releasing 8,000 to 12,000 mink and around 100 foxes into the wild. Thus followed seven and a half years on the run from the FBI, which culminated in the pair’s arrest after they were accused of shoplifting CDs from a California Starbucks.

Yet buried among the accusations was one the prosecution simply couldn’t prove. Young was a member of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) they said, a clandestine group of animal rights ‘extremists’ who attack companies in animal enterprise (food, vivisection, fur) via direct (read illegal) action. The FBI rates the ALF, alongside sister organisation the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), as its number one domestic terror threats. Al Qaeda comes in second. Two of the six most-wanted domestic terrorists in the US are ALF/ELF activists.

Since its inception in 1970s Britain, the ALF has caused hundreds of millions of dollars of damage to animal enterprises worldwide. Its mission statement: “To effectively allocate resources (time and money) to end the ‘property’ status of nonhuman animals.” Bomb attacks, arson and theft are all common methods of reaching this goal. Young chose the latter at a time when the fur trade was top of the ALF agenda. “We thought that fur was winnable,” he tells me across a crackling phone line. “We felt its collapse was imminent.”

But it wasn’t. Fur is back, and the ALF is facing crisis – despite the very real prospect that it never existed at all.

New York: a crowded subway car rattles along beneath the city. Above ground, it’s barely 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Below, New York Fashion Week has just ended, and the train is full of fashionistas returning from shows around town. Fifteen years ago, almost no-one below pension age would have been wearing a fur coat. This frozen evening there are a good half-dozen riders wrapped in mink or fox pelts.

“The perception of fur in general has changed,” veteran furrier Dennis Basso tells the New York Times for its annual ‘Fur Is Making A Comeback’ piece. “The day of the woman getting into the back of the limousine with the fur coat has totally changed. Today, she’s a modern young girl meeting girlfriends downtown. She’s on her way to the office, on the subway.”

There’s little arguing that this year’s Fashion Week saw a resurgence in the use of fur and leather. Carolina Herrera and Donna Karan showered their shows in fur, while younger designers like 21-year-old Mathieu Mirano, traditionally less likely to use fur, have been outspoken in their advocacy of animal products this year.

“This is almost the golden age in fur,” says fur marketer Charles Ross. To be honest, you’d be hard-pressed to counter him; since the protest-heavy 1990s, fur has become a US$15-billion business. Up to 50 million animals are killed each year for their fur, the majority of which are mink (food production, incidentally, claims a staggering 56 billion). Despite bans on fur farming in the UK, Croatia and Austria, the EU is still the world’s largest producer of fur, followed by China. Pelt production worldwide is thought to have risen by nine per cent last year.

Keith Kaplan is executive director of the Fur Information Council of America (FICA). It’s a freezing day when we meet just after a Fashion Week show. “So many more women are wearing fur now,” he says jubilantly. “I even saw a couple of guys wearing fur on the way here.” It’s Keith’s job to ensure celebs and designers are using fur. Naturally, then, he’s in high spirits. “Fur has been everywhere, and the biggest excitement has been how many young girls are adapting fur into their wardrobes.” The biggest increases have been in the use of fur trim, he says.

“Nobody has a right to cast their moral high ground on another,” says Kaplan of animal rights activists like Peter Young. “It’s all a matter of choice.” It’s an argument that’s flatly rejected by Ashley Byrne, of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA): “Most people agree that basic laws protecting the rights of animals are appropriate. No-one thinks that’s imposing one’s beliefs on others. It’s simply protecting those who can’t protect themselves.”

Back in 1996, a fur protester dumped a dead raccoon on Vogue editor and outspoken fur proponent Anna Wintour’s plate at the Four Seasons. It was common to see mink outfits splashed in paint on the runway, such was the vitriol towards fur. This year wasn’t just quiet but downright silent, save for some video campaigning by PETA and a spate of fur-store break-ins Vancouver, which some heralded as a precursor to direct action at the soon-to-follow Fashion Week south of the US border.

But none came.

“If the movement had sustained the level of activity that was present in the mid to late 1990s, I think the fur industry would be dead now,” says Young. “People got a little bit complacent. The fur industry had gotten so small it was almost invisible, so people directed their attentions elsewhere. “

“What you see now is a lot fewer fur farms, but the number of animals killed has not gone down,” he adds. “And that’s really the only metric that matters.”

Young now makes a living writing and lecturing on his beliefs, and remains adamant that the sort of activity that landed him in jail is really the only way to quickly bring about the end of fur farming: “If every celebrity in the country came out vocally against fur tomorrow, I still think you’d have enough people who would keep the industry afloat.”

So what of the ALF, a group that even the FBI admits is “loosely organised”? Do any digging and you’re unlikely to find much of substance, bar news reports, a website and the ‘Animal Liberation Press Office’, an outfit which lauds direct action while remaining officially separate. An emailed reply from the group thanks me for my interest but directs me simply to a torrent of videos, links and images, many shocking, of animal abuses it has chronicled over the years. Another contact is even more taciturn, telling me in no uncertain terms that I’ve “no chance” of speaking to anyone currently involved in direct action. Peter Young can speak out: he’s been convicted of his crimes. Elsewhere is silence.

Much of this paranoia relates to a controversial US law that, overnight, turned campaigners into terrorists. The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (AETA), made law in 2006, justifies huge sentences for any acts that ‘damage or cause loss to real or personal property’ or that ‘place a person in reasonable fear’, such as when extremist groups post letters threatening those they believe to be putting animals’ lives in danger. Opponents of the law argue that its ambiguity is a veiled attempt to lock down on any protest against animal cruelty. Whatever its efficacy, AETA has led many activists to batten down the hatches to anyone, including journalists.

“The ALF’s not an organisation at all, it’s more like a concept,” says Shannon Keith, an attorney who runs a non-profit organisation called Animal Rescue Media Education (ARME). Keith produced and directed the 2006 documentary Behind the Mask in an attempt to demystify the ALF, its history and its actions, speaking to founders in the process. “Basically, if you’re liberating animals and if you do so without harming individuals, then that action could be an ALF action,” she adds. “Usually these are illegal.”

Peter Young equally argues that the ALF is a brand name – just like the fashion houses and farms it tries to destroy: “I’ve received a couple of communiqués from people called ALF. But I have no connection to anybody.

“Because of the number of arrests in the past few years, the authorities are seeing that [direct action] really is a collection of totally anonymous individual people who act outside any sort of hierarchy or knowledge of what anyone else is doing.”

It seems that, as with Al Qaeda, the FBI is chasing something that, more likely than not, is little more than a well-chronicled set of principles.

Still, after several fruitless phone calls, I manage to arrange a video call with someone whose voice is altered and describes herself as ‘Antichrist’. Antichrist is a former model from Britain. I ask whether she can point me in the direction of anyone else involved in direct action. She cuts me off. “I wouldn’t know,” she says. “Even if I did know, you wouldn’t know about that kind of thing.”

Despite the UK’s banning of fur farms, Antichrist echoes Young’s anger that the anti-fur heydays haven’t pushed fur out of fashion altogether: “In the 1990s there were only four designers using fur. Now it’s up to 400. They got a bit arrogant, thought it was over.”

For Antichrist, though, who tells me about recent campaigns against Burberry and Harrods, the biggest issue right now is China and the increasing influx of ‘faux fur’ into Western stores that’s anything but: “You can walk down the street in London and see guys selling a bunch of scarves they’ll tell you are fake fur,” she says. “They just don’t know that it’s actually cat, dog, all sorts.”

Regulations in the Chinese fur industry, which despite its official position as the world’s second most-prolific producer is reckoned by some to account for over half of all fur globally, are notoriously lax. In 2010, a video by Swiss Animal Protection showed animals being skinned alive, their heads being kicked and trampled on, bloodied, skinless dogs writhing in piles and other atrocities condemned on all sides of the fur argument. (FICA alleged that the filmmakers were egging on their Chinese subjects, a report strenuously denied by the film’s director.)

Thousands of ‘faux fur’ items in Western stores, labelled as having come from Europe, have been discovered to contain cat, dog and raccoon. This has led to the tightening of labelling laws in the US, and the closing of a loophole that allowed products priced under US$150 (Dhs550) not to have their provenance disclosed.

There’s little chance of laws changing in China. Protesters are regularly followed and killed. And as anti-fur protesters have won legal battles in the West, they’ve pushed some unscrupulous Western traders to the Far East.

But that doesn’t mean that there haven’t been victories for the anti-fur movement. A ban on fur in West Hollywood is due to come into action this year, while Israel has banned fur altogether. Keith Kaplan isn’t convinced that either will make a difference: “Israel is a country where it’s always really hot. There’s no fur production. It’s a meaningless attempt by animal rights people to make a statement in a place where there wasn’t a market to begin with.”

Maybe that’s why, despite PETA’s best attempts to change people’s minds about fur, Young is still certain that the only way to beat the fur trade is direct action. “It would only take a handful of people risking their freedom, laying out a very targeted campaign and targeting lynchpins in the fur industry,” he says. “I think the fur industry could be collapsed in one year if the underground really focused its efforts.”

For now, though, the demand for fur seems as high as ever. In the ALF’s mind the demand is chattel to supply. And until that supply is destroyed, fur coats will always be worn on the subway.

Written by Sean Williams

Image: Corbis