Before Insta-influencers fronted brand campaigns, designers had their one true muse…

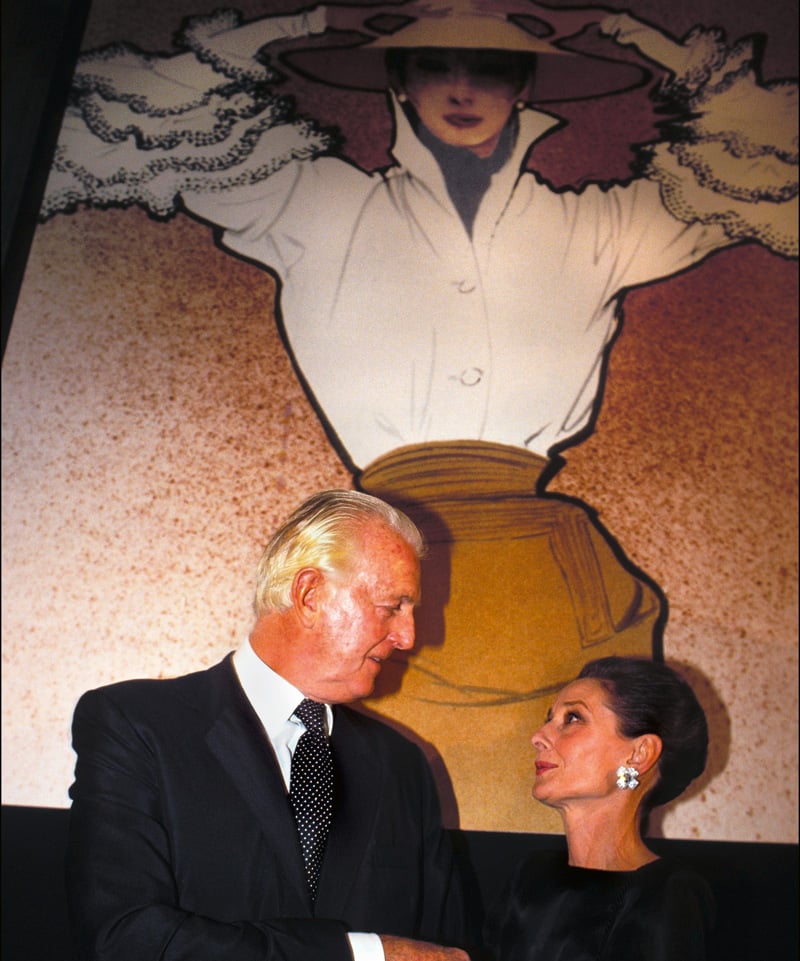

This is the story of how Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn’s relationship became the gold standard in the fashion industry.

Before there were ‘faces’; before there were ‘brand ambassadors’; before there was E!’s Live From the Red Carpet; before ‘American Gigolo’ and Armani (before Cher and Bob Mackie, or Alessandro Michele and Jared Leto); before there were Los Angeles offices and celebrity liaisons for every fashion brand; before there were influencers, there were Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn.

Read:

This royal-backed charity pampered four deserving Dubai women

How ‘proud feminist’ Meghan Markle plans to get to work

The original designer and his actress muse, Givenchy and Hepburn defined a relationship that has become the gold standard of almost every brand.

And although almost every obituary and headline since the news of Givenchy’s death in March of this year, at age 91, has referenced the relationship as core to his career, its impact went far beyond what it meant for the individuals involved.

Arguably, on the model of their 40-year relationship, an entire fashion/Hollywood industrial complex has been built. The question for me is whether either of them would necessarily recognise the connection, as deformed and industrialised as it has become.

It’s worth reminding ourselves, in the age of what increasingly seems like celebrities-for-hire — when dresses worn by one designer to enter an award ceremony get changed to dresses worn by another designer for the after-party and famous names profess undying devotion to a brand one season and then pop up in the ads of another brand the next — that once upon a time this was about two people who found in each other kindred spirits and worked together to craft two images: that of a woman and the man who dressed her.

And that once ‘muse’ when applied to fashion and artist, was interpreted in the classical Greek sense of the word, as opposed to as inspiration for hire, or for public pitching.

Givenchy and Hepburn found each other before either was really famous — the designer had only recently opened his maison; her first major movie had yet to be released — and they stuck with each other through seven films, from 1954 to 1987. He made not just the white dress she wore to win her Oscar for best actress in 1954 (for Roman Holiday) but her wedding dress (for her second marriage, to Andrea Dotti).

And so many betwixt and beyond that, in 2016, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague had an entire retrospective devoted to his work for the actress, called To Audrey With Love. In the show, Hepburn said of the relationship: “Givenchy’s clothes are the only ones I feel myself in. He is more than a designer, he is a creator of personality.”

It’s as good a description of the role that clothes can play in building an image as any I have ever heard. In return, she made the designer and his brand synonymous with a certain kind of elegance that could be both gamin and languid, encapsulated by the idea of the little black dress. Other designers made them, but when she wore them on screen, as she did in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Sabrina, she amplified the effect to such an extent that it echoed not just around the world at the moment the film debuted but over time.

When Givenchy introduced his perfume, L’Interdit, in 1957, she was its face because he made it for her, not because she was paid. And that is part of why the relationship worked so well: it was so mutually beneficial not just as a friendship but as a professional signifier.

When women bought Givenchy, they were also buying into a belief in long-term investment in elegance. That is why, as Hubert’s peers became known for their symbols – the pearls and camellias of Chanel; the New Look and Bar jacket of Dior – he was forever known for his muse.

He did more than dress Hepburn, of course. He dressed other famous women, including Jackie Kennedy, Grace Kelly and Elizabeth Taylor. He was one of the first designers to create high-end ready-to-wear, and a signature scent – and to see the future coming to fashion, and sell his brand to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton in 1988, when it had barely achieved conglomerate status. And he was an exacting tailor.

But his relationship with Hepburn loomed over it all, so much so that you’d think he might have chafed against it, although he never did. That came later, as other designers took his place and tried to assert a new identity for the house, and celebrities (or their agents and managers) began to realise that what had once been a mind-meld of taste between designer and muse could become a significant source of supplemental income. Although other brands have hewed close to the celebrity route, stacking the front rows of their shows and their ad campaigns with famous names, many of whom are also contracted to wear their clothes during public appearances a certain amount of times a year, it’s hard to think of any brand that has become so synonymous with a single artist.

Indeed, in 2013 the headlines about a Givenchy perfume campaign read: “Amanda Seyfried Is Givenchy’s New Face, Liv Tyler Out,” which pretty much says it all. This was during the period Riccardo Tisci was creative director, which also happened to be a time Kim Kardashian was often referred to as his muse (but she also was called a ‘muse’ for Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing, and her husband, Kanye West).

Read:

Arab supermodel Hind Sahli’s mission to change the fashion industry

Everything you need to know about Meghan Markle’s wedding dress

When Tisci left early last year and was replaced with Clare Waight Keller, Givenchy’s first female creative director, speculation was rife that she might be her own Hepburn (due in part to her personal aesthetic and charm). But she dismissed the idea, saying what interested her most about the relationship was the connection between a man and a woman – which she recreated by combining her men’s and women’s shows – and that it was reductionist to stick to closely to the Hepburn idea.

Thus far she has largely stayed away from any overt celebrity connection. Perhaps it’s impossible to recreate what Givenchy and Hepburn had. The digital world moves too fast; people’s attention spans are too short; we know too much about celebrity behaviour for it to have the same mystique and allure; no individual or brand wants to be so dependent on the other.

Perhaps that’s history. But theirs was a relationship that had content. And even today – especially today – content matters.

Words: Vanessa Friedman

Images: Getty