Today (April 20) marks the 15th anniversary of the Columbine High School massacre in Littleton, Colorado. But despite the wounds it left on America, a fight is still on for its legacy. Is it possible for Columbine to mean more than a random act of violence?

Darrell Scott told them everything. He told them about God, about money, about the media and about guns. About televangelists, million-dollar churches and Cain and Abel. He told them about his little girl, Rachel, and about how she had been killed while she sat on her school field talking to a friend. He told them about his son, Craig, who hid under a table and saw two kids die in front of him. He told them about compassion, forgiveness and love. And he told them to do something so his daughter’s life, and the lives of those 11 others, wouldn’t have been lost in vain.

It was a month since Columbine. In the 15 years that followed, little has been done.

Columbine was not the deadliest school shooting in United States history. Nor was it the first. But the massacre, in a sleepy Denver suburb on April 20, 1999, was a trauma that ruptured America across age, religion and morality. Films, books and reports have since dispelled many of the myths surrounding Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the murderers who eventually turned their guns on themselves. But the US is still reeling from the many more questions it raised about popular culture, guns and American violence.

For Darrell Scott they’re questions that have consumed his life ever since Rachel, then a bright-faced 17-year-old with long, brown hair and a deep-set spiritual curiosity, was gunned down while talking to a friend, Richard Castaldo. Castaldo, who was shot eight times, survived. Rachel was the first to die at Columbine. A few weeks later Congress called and asked her father if he’d speak at a judiciary committee. They wanted him to speak about gun control. He was still emotionally raw. “I told them I’d come on one condition,” he says. “Just that I could speak from my heart. I wasn’t there to talk about gun control cause I felt there’s much deeper issues than just passing more laws.”

Scott’s speech roused the nation and led to helm Rachel’s Challenge, an organisation that arranges talks and training to deal with schoolyard issues like bullying and depression. “Specially in those early days I’d speak in front of 20,000 people, 30,000 people at a football stadium, hockey stadium,” he says. “We began to realise the impact of Rachel’s story, especially on young people.”

Gun control laws have barely changed in Colorado since Columbine, despite lawmakers proposing almost 800 new laws in the wake of the tragedy. Ten per cent passed. The state still allows weapons to be carried in vehicles, and offers permits for concealed guns to be carried for protection. Gun laws have barely changed across America. Since the massacre there have been 153 school shootings, and 185 deaths. Some parents, like Tom Mauser, father of Daniel Mauser, who was also killed that day, have campaigned hard for gun laws to be tightened. Scott, a stocky, soft-spoken man with smart, grey-white hair, grew up in Louisiana. People there had guns. Some of his friends would stash them away in lockers during the school day so they could head straight out after to hunt squirrels, deer, whatever they could find. For him the answer is less clear-cut.

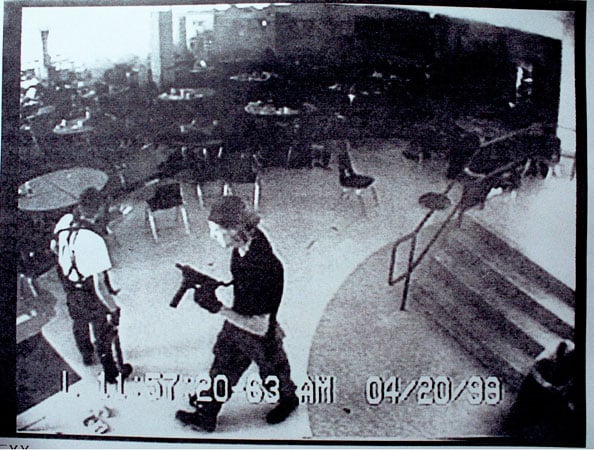

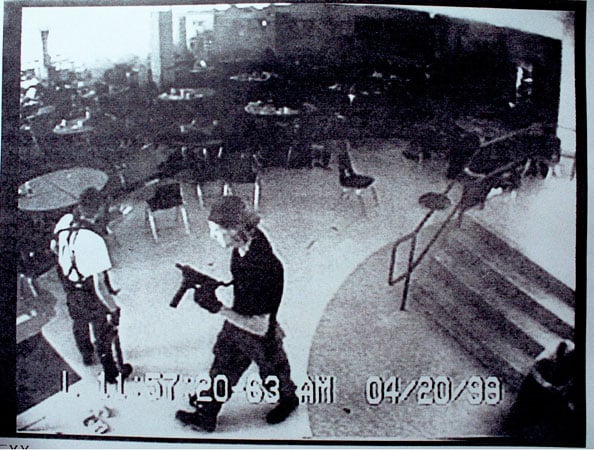

Columbine Shooters Eric Harris, Left, And Dylan Klebold Appear On A Surveillance Tape In The Cafeteria At Columbine High School On The Day Of The April Shooting. The Jefferson County Sheriff Played The Contents Of The Surveilance Tape As Well As Tapes Made By The Two Boys For The Media After Time Magazine Reported On Them The Week Of December 13, 1999.

“No matter what you say you polarise yourself,” he says. “There are two extremes. One is that guns are to blame for all of this, let’s get rid of every gun in America. Which is a very impractical goal because it’s never gonna happen. Secondly would be that you can’t pass any law on anything – no background checks, no anything, because of the second amendment (which entrenches Americans’ rights to bear arms). And I think both those extremes are asinine.

“It’s like Pandora’s Box that you can’t bring it all back,” he adds. “That’s why I don’t get involved in that stuff.”

Scott is an ordinary guy who suffered an extraordinary tragedy. Littleton, a town of just over 40,000 people south of Denver, is little different. Founded in the wake of the 1859 Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, the town is a pretty grid of old municipal blocks and cute, tree-lined streets. A short drive west is the Rocky Mountain National Park. The feel of quiet permanence is everywhere.

But on April 20, 1999 the quiet was shattered. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold entered Columbine a little after 11am on an usually bright, warm day. They were armed with 9mm weapons and two 12-gauge shotguns. Propane bombs they’d planted in the school cafeteria had failed to ignite. Harris and Klebold shot indiscriminately as they moved, jeering at hidden kids and teachers before they killed them. Some played dead; others stole away under desks, chairs and computer tables. The murders were relentlessly random, despite theories they were based on faith.

Steven Curnow, a skinny 14-year-old who dreamed of a life in the Navy, was killed when Harris strolled past the desk he was under and fired his shotgun without looking. William David ‘Dave’ Sanders, a computer teacher and varsity coach, was shot as he ran down a corridor evacuating children. He was the only teacher killed that day. An hour after they entered the school, Harris and Klebold killed themselves. The pair had planned for years, and dreamed of a death count greater than the Oklahoma City bombing that occurred four years before, and which killed 168 people. They had originally planned their attack on its anniversary. If they’d been better at timing the propane bombs 600 may have died.

In the wake of the disaster, fingers were pointed everywhere. Some aimed vitriol at video games. Others at guns, goths, South Park and Marilyn Manson, who refused to be drawn into the debate.

People looked to the Klebolds and Harrises, who quickly became social pariahs for the actions of their sons. Susan Klebold described the moment she discovered her son was a serial killer, to Oprah Winfrey several years later She said. “My husband had told himself that if he found the coat, Dylan couldn’t be involved. He’d torn the house apart, looking everywhere. No coat. When there was nowhere left to look, somehow he knew the truth.

“It was like staring at one of those computer-generated 3D pictures when the abstract pattern suddenly comes into focus as a recognisable image.

“In the weeks and months that followed the killings, I was nearly insane with sorrow for the suffering my son had caused, and with grief for the child I had lost,” added Klebold. “Much of the time, I felt that I could not breathe, and I often wished that I would die.”

In a book released in 2012, Klebold opened up about Dylan’s actions, and claimed the way she was treated helped her understand him better: “What I’ve learned from being an outcast since the tragedy has given me insight into what it must have felt like for my son to be marginalised. He created a version of his reality for us: to be pariahs, unpopular, with no means to defend ourselves against those who hate us.

“I could read three hundred letters where people were saying, ‘I admire you,’ ‘I’m praying for you,’ and I’d read one hate letter and be destroyed,” she added. “When people devalue you, it far outweighs all the love.”

Dave Cullen’s 2009 book Columbine recounts the attack, and the 10 years that followed. His work unravelling the characters of Harris and Klebold won him dozens of awards, and has shed light on the issue of teen depression, that was largely ignored after Columbine. “Most of these school shooters are deeply depressed, and the biggest thing they have in common is a suicidal depression,” he says. “It’s much more sensible to view most of these shootings as suicides, vengeful homicide-suicides, in terms of understanding them.

“I think the video games/messed up (theories) came and went,” adds Cullen, who was shocked by the compassion of victims’ families. “But the idea of bullying is very prominent, and there’s still the idea that ‘you pushed these kids too far, you hurt them and then they struck back.’ That’s usually not what’s going on. I think it’s foolish and uneducated to make assumptions that they must have been driven to it, looking for external problems rather than say that these people had problems and weren’t dealing with them.”

Klebold, Cullen explains, was a depressed, reclusive young man well before his awful act. Harris, meanwhile, was a textbook psychopath. One of his journals, released six months after Columbine, opened with the line “Kill mankind. No-one should survive.”

“We hate n*ggers, sp*cks … and let’s not forget you white P.O.S. [pieces of sh*t* also,” wrote Harris. “We hate you…You know what I hate? Racism. Anyone who hates Asians, Mexicans, or people of any race because they’re different.”

Rachel Scott kept a diary too. Six of them. She had a copy of Anne Frank’s Diary and wrote inspirational messages in her free time. “Some of them are pretty profound,” says Darrell Scott, who breaks into one: “‘Don’t let your character change colour with your environment; find out who you are, and let it stay its true colour.’

“She also had a sense that she was going to die at a young age,” adds Scott. “She told some of her friends about it, she wrote about it in one of her last poems she wrote, she said: ‘I’m dying, slowly my soul leaves. It isn’t suicide, I consider it homicide, the world you have created has led to my death.’ And that sounds morbid when you quote it but it wasn’t. She wasn’t obsessed with death and she didn’t have a morbid personality. It was almost like a premonition that she was going to die young, and at the same time she’d save millions of lives, she wrote that on the back of her dresser with an outline of her hands. The things that she said have become reality.

“It’s wonderful to see that her life has counted. If I died today I would die knowing that I fulfilled my, not just a duty to her, but my celebration of her life.”

Tragically, though, history often repeats itself. And just 13 years after Columbine James Holmes walked into a cineplex in Aurora, Colorado – just a short drive from Littleton – and killed 12 people. Later that year, 2012, 26 children and teachers were shot dead at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut by Adam Lanza. Hands have been wrung and debates rage on at a government level, but it seems as if little is being done to quell the long line of gun victims in America.

Darrell Scott prefers not to dwell on government action, though. He’s not sure it helps as much as solid grass-roots involvement with children, and the many issues flung at them on a daily basis. Counteract the problems children face, he says, and Rachel’s life, and all the others lost at Columbine 15 years ago, will have left a great legacy. “I would like people to focus on the positive solutions. Understanding one another. Timeless compassion, these are things my daughter represented. Also to pay attention to those kids who are withdrawn, antisocial. Most of the time they’re the shooter. If we could take a little more time to help people be social, people to become more interrelating, that’d go a long way.”

Columbine is not, Scott has proven, a mindless tragedy.

Words: Sean Williams

Image: Getty