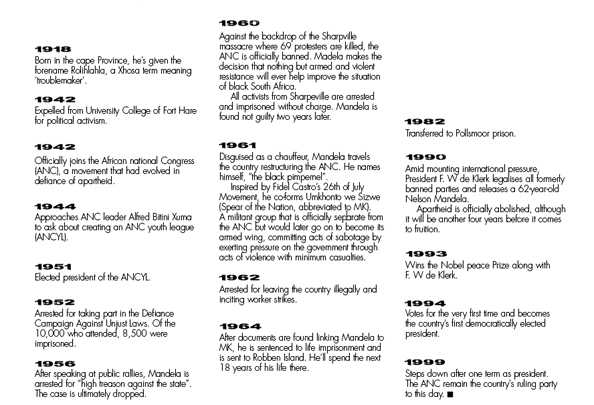

Freedom fighter, prisoner and inspiring leader, sadly on Thursday December 5 the legend Nelson Mandela passed away. Leading his country, South Africa, out of decades of apartheid, he was a real-life hero. Here, we take a journey throughout South Africa’s past, present and future through six personal stories and landmark sites of Nelson Mandela’s life.

From jailed political activists to survivors of apartheid massacres, from acquaintances and relatives of Mandela to ordinary students, housewives and retirees, Nelson Mandela has touched and affected the lives of so many in South Africa and the world.

Here six people recall the legacy of Mandela through their personal stories, where love, sorrow and hope intertwine with landmark events in the history of the country. Each of the interviewees is photographed in front of one of the most relevant sites of Mandela’s life.

ROBBEN ISLAND

Thulani Mabaso on Robben Island, where he was imprisoned for six years for membership of the ANC military wing.

“We all played our part, from the families who lost their husbands and children, to the guys who died or were disabled in the struggle. There were many Nelson Mandelas in our history,” says Thulani Mabaso, 50, speaking about the man credited for having freed South Africa from the racial segregationist regime of apartheid.

In 1981, Mabaso was sentenced to 18 years in prison for setting up a limping mine that lightly wounded 57 people at the Defence Force building in Johannesburg. Now a stocky, well-built man of 50, at that time Mabaso was a member of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC), the main political organisation led in the 1990s by Nelson Mandela and opposed to the white-dominated apartheid government which ruled South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

“I could have killed people, if I wanted to. But our goal was to make a statement,” says Mabaso remembering the attack, for which he spent seven years in Robben Island, together with Mandela. Mabaso was one of the last prisoners to be released in 1991, following the end of apartheid laws: after arriving at Cape Town harbour in the first days of July, he boarded a plane to Durban, where, after being unbanned, the ANC was having its first national congress in 32 years. “Nelson Mandela had wanted me there,” he reveals proudly. “He greeted me warmly, before introducing me to all the party leadership. It was a great moment.”

Originally from the Kwazulu-Natal region, Mabaso still has vivid memories of the reason that pushed him to join the armed struggle. When he was eight, his family was forcibly removed from Dannhauser, a peaceful countryside village, where people used to live off farming, grazing cattle and fetching water from the river. The apartheid government, which was forcing the black population into designated areas called ‘homelands’ to enforce racial separation and reserve the most fertile and economically profitable land for whites.

From a peaceful and happy life, Mabaso was catapulted into an arid and dusty environment, where eight families had to share a shanty house made of asbestos. At school, there was one textbook shared with 80 students. “All our chickens and goats had been confiscated. We had to sleep on the floor,” says Mabaso, his voice rising in anger. Nowadays, Mabaso is a very different man, working as a tour guide at the Robben Island Museum. “This place evokes so many good and bad memories for me. I still have nightmares,” he adds. “But I never regretted my decision of joining the armed struggle. Life under apartheid was bad.”

SHARPEVILLE MEMORIAL

Vuyiswa Moalosi pictured beside the Sharpeville Memorial, built in honour of the 69 people killed in the Sharpeville massacre of March 1960, in Sharpeville, South Africa. The massacre led to anti-apartheid organisations like the ANC taking up armed resistance.

“Apartheid might be over, but its remains are still here,” complains Vuyiswa Moalosi, 58, an outspoken woman living in the township of Sharpeville. Here, on March 21, 1960, 69 people were gunned down by the police while protesting against the use of the pass book, a discriminatory document all blacks had to carry when outside their homelands or designated areas.

At the time of the massacre, one of the worst in South African history, Moalosi was only five. “It was so terrible that even dogs didn’t dare to bark,” she recounts, tears filling her eyes. “I remember a family running up the street, crying, after they had lost a wife and a daughter.” Today, the site of the massacre hosts a memorial made of metal poles, one for each victim, while March 21 is now celebrated in South Africa as Human Rights Day. On December 10, 1996, Mandela rendered homage to the victims by signing the new Constitution in Sharpeville: in a small stadium crammed with cheering people, he announced that there would be no more violence, death and killings.

“Every morning, I had to pass over corpses to go shopping,” says Moalosi who lost her two sons in the previous years, during clashes between police and youths. “But that day at Sharpeville stadium I was so happy. I was just sitting next to Mandela… It was one of the happiest days in my life.”

Nineteen years after the advent of democracy, Sharpeville is still a desolated network of one-storey houses and shacks, where economic opportunities are few and unemployment is rife. “The people who fought for South Africa are among the poorest today,” she complains. “While the widows and widowers of 1960 didn’t get any compensation, the black people who nowadays got rich don’t care about the rest of us.”

In 1994 there was a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of white South Africans, fearful of a payback time that never came. Scores of factories closed down, leaving the local population with no jobs. “I feel betrayed by whites,” continues Moalosi. “Some of them simply didn’t want to be ruled by blacks. I don’t feel they belong to South Africa.”

ALEXANDRA TOWNSHIP (JOHANNESBURG)

Isaac Mangena pictured outside the house where Nelson Mandela first lived in when he arrived in the town of Alexandra in Johannesburg.

“Mandela remains a hero, a unifier and a darling to everyone. Who can forget his humility, his charm and his brilliant mind?” Thirty-five-year-old Isaac Mangena can’t hide his emotions while speaking about the man who freed South Africa from apartheid. “People here in Alexandra feel they own a ‘share’ of Mandela,” he continues. “When he dies, there will be sadness and shock. A part of Alexandra will die with him.”

A buzzing township nestled among the northern suburbs of Johannesburg, Alexandra was the first ‘home’ where Mandela settled when he arrived in town in 1941. The township still continues to attract people from rural areas who want to try their chances in the economic capital of South Africa, just like Mangena, a former journalist now employed as spokesperson for a human rights agency. Although he and his family come from Limpopo, the rural province bordering Mozambique, Mangena considers himself a proud son of Alexandra, where he has lived for more than 20 years.

He still has his dearest friends here, with whom he spends most of his weekends eating, drinking and dancing. Above all, this is the place where, on February 11, 1990, news reached him that Mandela would have been freed from prison, after 27 years of detention. Due to the information blackout imposed by the apartheid regime, Mangena, who was 16 at that time, had never seen the face of Mandela before. He believed in his liberation only after seeing cars with the banned African National Congress (ANC) flags driving around the narrow roads of the township.

The joy for the now foreseeable end of the apartheid regime lasted for months, and was so overwhelming that, as he says with an innocent smile, “neither me nor my friends managed to pass our exams that year. But nobody cared about studying at that time”.

MQHEKEZWENI

Nozolile Mtirara sititng near Mandela’s teenage house, in Mqhekezweni. Mandela lived here from age nine until 18.

An old, 92-year-old woman sits calmly on a plastic chair in the garden of one of the few plastered houses of this village, lost in the countryside of the Eastern Cape region. “I’ve always seen Mandela as a father figure, since the first time we met,” she says, looking at three of her young nephews playing around in the garden. In 1945, Nozolile Mtirara married the cousin and childhood friend of Mandela, Justice Mtirara, and moved to Mqhekezweni, the village where Mandela had spent most of his childhood under the guardianship of the local regent and Justice’s father, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo.

“Justice and Nelson Mandela were very close. My husband and he grew up together, and did everything together,” she says. Their bond was so close that, when they discovered that Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo had arranged a double marriage for both of them, the boys fled to Johannesburg in 1941. “They sold two of the Chief’s cows to a white guy in order to fund their trip. He had to go there and buy them back,” remembers an amused Nozolile, who was one of the two girls who had been “refused”.

One year later, Mandela was forgiven by the Chief, who died shortly after. After returning to Mqhekezweni for the funeral, Justice decided to settle there and marry Nozolile, according to his father will, and so the two best friends parted. When Justice died in 1974, Mandela was in Robben Island. He was prevented from attending the burial ceremony, so he returned to Mqhekezweni when he was released from prison, in 1990. That was the first time Nozolile met him. “My house was built by him, as a thanksgiving for having spent his childhood here,” reveals a grateful Nozolile.

Mandela and Nozolile saw each other many more times, her being the only living bond between Mandela and Chief Dalindyebo. “The Mandelas treat me as part of their family. I am one of the few people who are allowed to visit their house in Qunu,” she says.

LILIESLEAF FARM (RIVONIA)

Celeste De Lang pictured at Liliesleaf Farm, in the Rivonia suburb of Johannesburg. Liliesleaf Farm was a hideout used by the ANC memebers, including Mandela. Nineteen ANC leaders were arrested here in 1963

Celeste De Lang, 69, is a charming woman living in Spring, a few kilometres away from the farm where Nelson Mandela, already a wanted man, used to hide in the early 1960s, posing as a worker named David Motsamayi. The farm was used as a clandestine meeting place by the most prominent anti-apartheid activists of that time, and finally raided on the July 11, 1963, by the police.

Nineteen people and compromising documents were seized. They where instrumental in sentencing Mandela and seven other African National Congress members to life imprisonment at the Rivonia trial.

“I first heard of Mandela when he was arrested. He was presented as a very young and angry man. At that time, overthrowing apartheid seemed impossible,” De Lang remembers. “But the example he set when he was released was amazing. His forgiveness was mind-blowing.” Despite coming from a family of English origins, De Lang and her family never supported apartheid. “My dad had a bakery and he always treated the black people working for him as colleagues,” she continues, adding that they would always exchange gifts for special occasions. “When I got married, I received a live chicken from one of my father’s workers. It was beautiful and very emotional.”

Like many young whites of that time, though, she was never active in politics and didn’t speak out openly against apartheid. The only time when she wanted to participate in a rally against the regime, she was locked for four hours, inside a university class by her teacher, who didn’t want her pupils to get arrested.

“We were quite afraid of stepping out and fighting for what we believed in,” she admits, with a hint of regret in her voice. “The apartheid police were aggressive. We were all scared of ending up in the trunks of their armoured vehicles.”

MANDELA CAPTURE SITE MEMORIAL (HOWICK)

When Nelson Mandela was stopped by a police patrol on the outskirts of the hilly tourist destination of Howick on August 5 1962, he could have never imagined that would’ve been his last day of freedom for many years to come.

To remember the event, a particular artwork was inaugurated in 2012. A tiled path leads through an embankment, towards a series of 50 spikes that compose the face of Nelson Mandela. The site is visited by dozens of visitors everyday. Among them are Jackie Naidoo, 53, and Fiona Rangan, 46, both of them mothers of three. “We brought are children to this site to show and teach them the story of Mandela,” says Naidoo. “He guided his people towards freedom,” says Rangan. “The way he forgave his oppressors after 27 years of captivity really freed us all. That will be his best legacy.”

Both women come from the nearby city of Pietermaritzburg, and have known each other for the 23 years. Being of Indian origin, they were classified as ‘Asians’ under apartheid. “We couldn’t visit certain places or beaches,” remembers Rangan. “If we wanted to go to a tea garden, a waiter would chase us away even if we had enough money to pay”. When apartheid fell one of the first things they did was visit a tea garden. “I also sat on a bench with a ’whites only’ inscription on it,” she continues. “It felt so good.”

Words: Matteo Fagotto

Photography: Andrew McConnell (main image: Getty)