Jonathan Yeo’s latest art exhibition, at the National Portrait Gallery in London, explores the real meaning of celebrity, uncovering an unconventional idol in the process. If you’re in the UK capital be sure to pay a visit before exhibit closes on January 5.

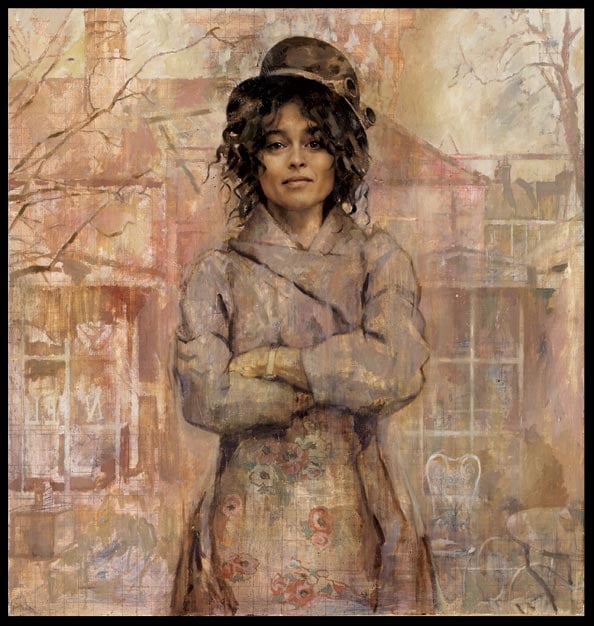

Walking through artist Jonathan Yeo’s exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery feels like a who’s who of A-listers – actors, singers, politicians, models and gentry stare down from grand canvases adorning the walls. Some have earned their place through birthright, others through meticulous publicity campaigns, and many through honing a thespian talent. Sienna Miller, Kevin Spacey, Helena Bonham Carter, Nicole Kidman, Prince Philip, Jude Law: the list of Jonathan’s sitters reads like one long name-drop.

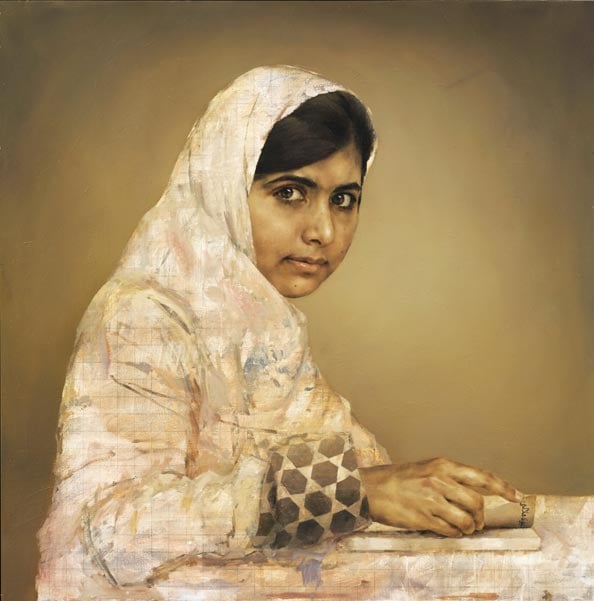

Many of these celebrities wouldn’t be in the exhibition had they not chased their dream in the entertainment industry. But sitting among the stars, draped in traditional Pakistani dress, is a teenager who earned her place simply by seeking an education. In our world of instant celebrity, fame comes quick, and it was no different for this 16-year-old – but for her, stardom came with the pull of a trigger.

Malala Yousafzai’s journey from ordinary schoolgirl to published author, education activist, and youngest ever nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize, is harrowing. Though Malala spoke up to the press about women’s right to education, which is banned in some parts of Pakistan under Taliban law, nobody expected the terrorists to target a child. But on October 9, 2012, two gunmen boarded a school bus in the Swat Valley region. One of the men barked: “Who is Malala?” before shooting her in the head at point blank range. And it seems that since that day, the rest of the world has been asking the same question.

To artist Jonathan Yeo, who has made a career out of painting famous faces, there is no doubt that she is a famous figure. “‘Celebrity’ often has negative connotations,” he explains. “We should perhaps return to the idea of it suggesting a person who should be justly celebrated for their actions. And in that sense, Malala is certainly a figure we should celebrate.” Yet it seems that this formula isn’t widely accepted – Forbes’ list of the Top 100 Celebrities is calculated using earnings and media coverage. There is no box for talent or admirable actions.

In spite of some of the shortsighted beliefs, Jonathan insists it was obvious that Malala’s portrait should be displayed in his exhibition among the luminaries. Though he’s had the opportunity to paint many Hollywood greats, he cites Malala as one of his favourite sitters. “It’s always nice to paint Hollywood stars,” he says. “But the most exciting sitters are always the creative ones; the real artists are those who will change the world through their politics.”

And changing the world is high on Malala’s agenda. While fellow sitter Sienna Miller’s most famous award to date has been a Razzie for Worst Supporting Actress, Malala has already been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize; she’s met US President Barack Obama, opened the largest library in Birmingham, UK, been awarded the International Peace Award and won the International Children’s Peace Prize – and she’s only been out of recovery a matter of months. In true celebrity fashion there is, of course, a book deal worth seven figures – Malala’s recently published memoirs are believed to have netted around US$3 million.

Jonathan Yeo’s works at the National Portrait Gallery include images of celebrities like Helena Bonham Carter

Opinion columns have been rife with rumours that she’s acting as a mouthpiece for a PR campaign, or that this role as an ambassador for education has been forced upon her, and Jonathan admits he had reservations. “We were lucky enough to meet at her family home,” he recalls. “I was inspired by her story, fascinated by her extraordinary position, but I was apprehensive about finding someone who didn’t want to be in the position she was in… that maybe she was pushed into it.” Those reservations were quashed when he met her in her own environment. “I understood that she is being supported to do what she wants and she has the potential to make amazing things happen.”

This potential is something that women in northern Pakistan don’t often have the privilege of. Though Malala’s hometown, Mingora, is no longer officially under Taliban rule, the terrorist group continues to impose strict rules and punishments. As well as banning women from education establishments, women who don’t dress in accordance with Taliban rules are publicly beaten and women are banned from working outside their own homes. Malala told BBC News that this is why she decided to continue going to school: “I didn’t want my future to be just sitting in a room, imprisoned in my four walls and just cooking and giving birth to children. I didn’t want to see my life in that way.”

For this reason, Malala is a role model for women, teenagers, campaigners and political figures across the globe. Jonathan describes this as her “totemic profile”, which is what fascinated him from the onset. “A totem is a symbol that is emblematic to a certain group of people,” he says. “All these different audiences, all over the world, are projecting their ideas about what she should be upon her.” Jonathan is keen to emphasise that Malala is more than public figure. He adds: “These [ideas] go far beyond what she has intended herself to be. We have to be aware of Malala as a symbol, but most importantly as Malala the young person; the individual.”

In our image-saturated society, Jonathan captures a pause in time that paparazzi snaps of celebrities don’t. However, as a perfectionist, he doesn’t feel that it represents the youthful side of Malala that he saw. “Looking at the painting now, she seems more mature and wise than what I had sat in front of me; reading her books and preparing her homework.” It would be fair to say that the strong look that Jonathan has depicted represents her public persona. He says: “Her vision and sense of purpose is much more consistent with a more grown-up and statesman-like personality.”

A grown-up persona is necessary with one of the largest terrorist organisations in the world as an enemy. A Pakistani Taliban spokesman recently told AFP: “We will target her again and attack whenever we have the chance.” For Malala this threat isn’t enough to scare her into silence and she continues to run The Malala Fund to support women’s education throughout the world. Picturing confrontation with the Taliban, she said: “I think of it often and imagine the scene clearly. Even if they come to kill me, I will tell them what they are trying to do is wrong, that education is our basic right.”

As Jonathan Yeo put it, Malala is totemic. To terrorists she is a criminal, to newspapers she is a fascinating story, to activists she is a role model, to suppressed women she is a beacon of hope. Even Jonathan couldn’t quite capture her in her entirety. Is she the new face of celebrity or just a normal teenager? Perhaps the answer lies in the Taliban gunman’s question, “Who is Malala?” and the young girl’s educated retort, which is the title of her memoir: I Am Malala.

Jonathan Yeo Portraits is running at The National Portrait Gallery in London until January 5, 2014. For more information, visit here

Images: Copyright Jonathan Yeo