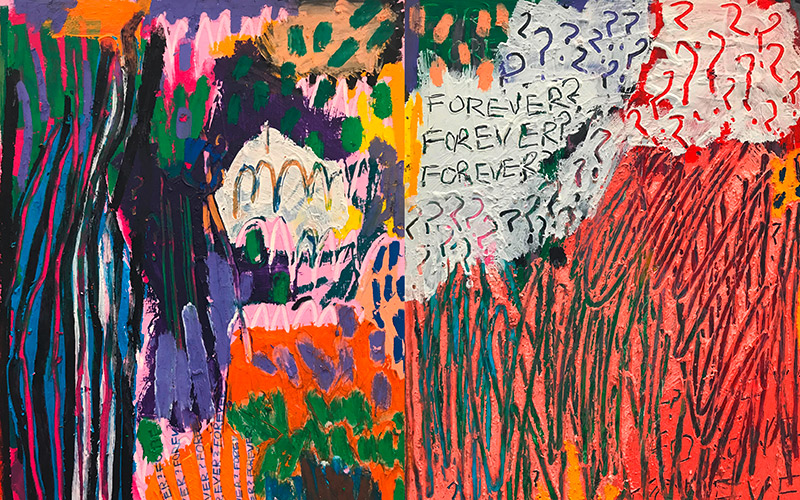

Painted glories

Aidha Badr is a painter from Brooklyn, New York living and working in Kuwait. She studied painting at Binghamton University in New York state and was formally trained as a portrait painter, but has recently begun exploring a more honest style of painting that she feels truly represents her inner life. A mixture of memories, time, place and life experiences serve as inspiration for her work

ALSO READ:

We sit down with leading Middle Eastern political artist Kinzy Al Saheal

Where do you find inspiration?

My art is completely internally driven. My most animating drives come from my nostalgic tenderness towards the past and I use that to sentimentally create work that fixates on substantially existent and phantom recollections, the wade of the ever-diverging chasm between our long-term memories recycled through the short-term memory and vice versa. The tremendous momentum in memory, influenced by time, place and experience courses through my most recent work. Some memories course through me more than myself, and some suffice for me where myself withers.

What is the main context of your work?

Purity, honesty, and virtue. Nothing is formulaic or constrained, it all comes from my own temperament. Breaking the infinitesimal space that separates us from vulnerability but in a playful way, like a mother’s tender laugh at the vulnerable silliness of her child. My work focuses on humans and interpersonal relationships and is not entirely solipsistic. I focus on an attachment to objects, objects I own, objects I’ve seen and objects I can’t be sure I’ve seen. Nonetheless they all have the same echo, the same kind of attachment because in my simplicity, I believe things to be ephemerally permanent. All remains, nothing is forgotten. I often use language as a tribunal on to which all of my thoughts and memories can manifest.

Your artwork contains a lot of enigmatic statements. What messages are you hoping to convey?

That it’s okay to be vulnerable. Vulnerability is a trait that is very underrated and often discouraged. The willingness to be vulnerable is the disposition to be more empathetic and understanding. I refuse to settle with the myth that pain is the sole source for our art – it’s far too complex to be reduced to that because vulnerability is the single universal condition that makes us utterly human. It is also the same condition for which we are immensely afraid, and my body of work aims to explore emotional vulnerability, which is often characterised as a female trait, one that positions women as, at best, diminutive and dependent, and at worst, neurotic and unhinged. Being emotional isn’t synonymous with being weak, and vulnerability doesn’t need external justification, but is a strength in and of itself and that is what my art aims to explore. What I have learned and strive to depict in my art is that being vulnerable and forming connections can be healing.

What do you love about artists in the Middle East?

I love the ethos of solidarity. I love the support and endeavor I get, but the effect is one of familiarity. We all need that when we get bent out of shape by our own postures and gestures whether or not you’re an artist. I love how some of them look constructively at culture instead of ripping it off for scraps of inspiration, which kind of gets grating after a while.

The female figure is important in your artwork. What do you love about the symbol of a woman?

There is a kernel of indestructible value to this question that is almost comparable to the bond I have with my mother, a true Dakini and the incarnation of stewardship. Understanding why my mother is the way she is has given me a kaleidoscopic lens into everything a woman could be. Women are more about genuinely connecting with other human beings, realising themselves as mothers and transcending that metaphysical relationship. This is what I feel I need to showcase as their milieu. I love women for their communion, their fragility, and empathy.

Media: Supplied